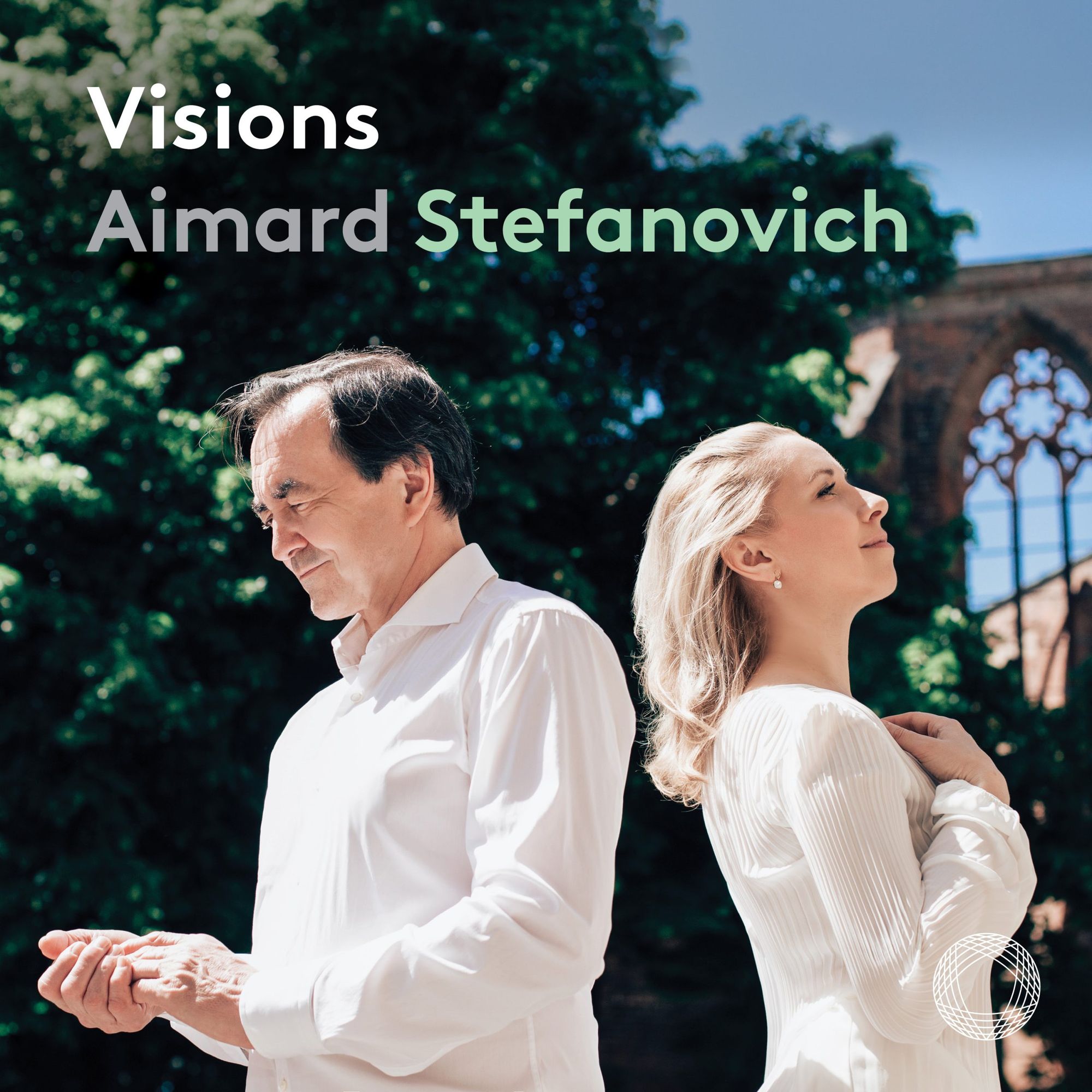

Visions: Tamara Stefanovich and Pierre-Laurent Aimard

A terrific disc. Unmissable

Tamara Stefanovich and Pierre-Laurent Aimard return to Pentatone wih this CD, Visions. The main body comprises Messiaen’s 40-minute Visions de l‘amen (1943) for two pianos, followed by Enescu’s Carillon Nocturne, Knussen’s Prayer Bell Sketch and “Clock IV’ from Sir Harrisoin Birtwistle’s Harrison’s Clocks. It is the sound of bells that prevades the disc - no Rachmaninov, but a carillon and a prayer-bell.

If anyone wants an entry point into the music of Olivier Messiaen (1908-1992), look no further than Visions de l’Amen . It is mesmeric, a deeply involving listening experience. As Tamara Stefanovich puts it:

Messiaen is a colour sorcerer, light architect and time illusionist. The acoustical drunkenness paired with the need to build a sound cathedralwas for me a magnet from the first time I heard “Visions”. Pierre-Laurent and I played both parts respectively and it seems this fact and constellation makes for a reading of complete commitment to biolding a structire from all sides.

As with constructing physical bells, you have to allow alchemy of matter and ether to vibrate in a mystical way, and this is needed in today’s world - breath and visions should guide us.

Pierre-Laurent Aimard is no stranger to the work - he turned pages for performances by Yvonne Loriod and Messiaen himself, and worked on the score with the composer. “If having a home really means anything, then this piece is my home,” he says. Of course, Classical Explorer recently published an interview with Pierre-Laurent Aimard, you might wish to explore.

This performance is held within a perfect piano recording - present, clear, with believable persepctive. It needs to be, given its basis - we need to hear the bell references (invocations of overtones and so on) and that can only happen via a crystal clear recording.

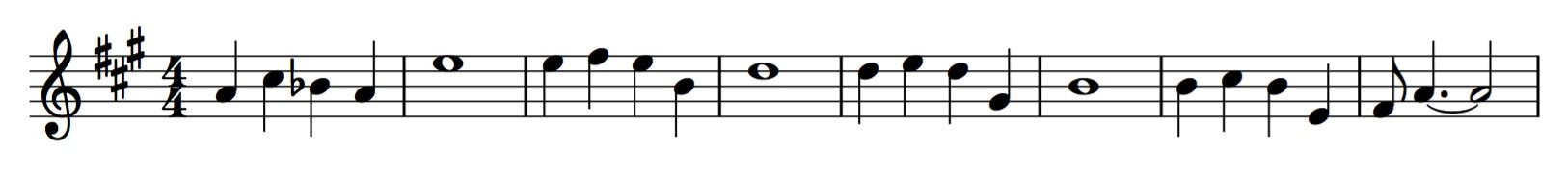

In the first piece, “Amen de la Création,” the second piano ahs the so-called “Creation” theme, while the first offers a rhythmically coplex counterpoint. This dynamic, of the second piano having the melodic material, is typical of this work. Here is the “Cration theme” (credit Yuval Filmus - Own work, CC BY-SA 4.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=48615902):

Rhythm is a vital part of Messiaen's work. We hear its complexity - which often is a dancing complexity - perfectly in the second piece, “Amen des étoiles, de la planète á l‘anneau”:

Messiaen’s harmonies, too, are deeply expressive - the chords he creates for “Amen de l’agonie de Jésus” are perfectly judged so that we hear the pain; and how they become shot through with light later. Even in agony, be it on the Cross or elsewhere, there is always the capacity for light, for hope, seems to be the message.

Ecstasy, too, is part of Messaien’s vocabulary, a religious ecstasy that is hard to miss in Aimard and Stefanovich’s performance of the “Amen du Désir,” the longest of the work’s seven panels. This is spectacular Messiaen playing - not just in terms of virtuosity. Notice how, just after the six-minute mark, a section tails of beautifully - exquisitely, even. Such musicality is a necessity in Messiaen’s music, as is the ability to contrast gesture against continuity. We heard that continuity in the long lines of the first movement above - while the gestural certainly informs the penultimate movement, “Amen du Jugement,” superbly delivered by Stefanovich and Aimard.

And as for thso bells, here’s the final movement, “Amen de la Consommation”:

Pierre-Laurent Aimard has said that, “If having a home really means anything, then this piece is my home,” and that sense of resonance is strong here. We hear in the final “Amen de la Consommation” a sort of Holy Joy as the carillons get ever more complex around the main theme:

This performance alone is worth the price of the disc. Visions de l‘Amen takes up some 51 minutes of disc space, and predictably from Stefanovich and Aimard, the couplings are perfectly judged.

Worth noting, too, that Pentatone allows the end of the Visions to resonate on - a detail that has huge emotional impact. It allows us to savour - and recover from! - the sheer intensity of that finale before the next piece, George Enescu’s Carillon Nocturne (the seventh movement of the Suite No. 3, Op. 18, ‘Pièces Impromptues’). This is performed by Aimard. The sense of freedom is itself a compositional masterstroke, as it is all carefully notated; but the other masterstroke is the bell invocations themselves. We really hear the overtones while we are beguiled by the harmonies (they are complex, but the dissonance is never harsh):

The Southbank Centre’s celebration of the music of Oliver Knussen (ingeniously entitled OK!) was a reminder of the stature of this composer. Composed as a tribute to the Japanese composer Toru Takemitsu, Prayer Bell Sketch (1997). Knussen said that, for him, the work comprised

... recollections and rearrangements of a few simple bell sounds which, to me, resonate with memories of a dear friend and wonderful composer

The work indeed holds multiple beauties, all of which are teased out by Stefanovich and Aimard. Hypnotically beautiful, ephemeral, elusive, this is great music, winningly delivered by Tamara Stefanovich. Finally, some Birtwistle performed by Aimard, a composer previously represented on Classical Explorer by Nicolas Hodges’ performance of Variations from the Golden Mountain, and a disc of chamber works on BIS. Here we have part of Harrison’s Clocks (1998), ‘Clock IV’. The initial gesture of descent brings to mind similar gestures in the Messiaen. But of course Birtwistle is his own man. The piece was inspired by a book about John Harrison’s invention of the marine-chronometer, and Birtwistle called ’Clock IV’ one of his “chiming pieces”. Full of dynamic contrasts (from ppp to ffff), this is muscuularly powerful music.

A terrific disc. Unmissable.