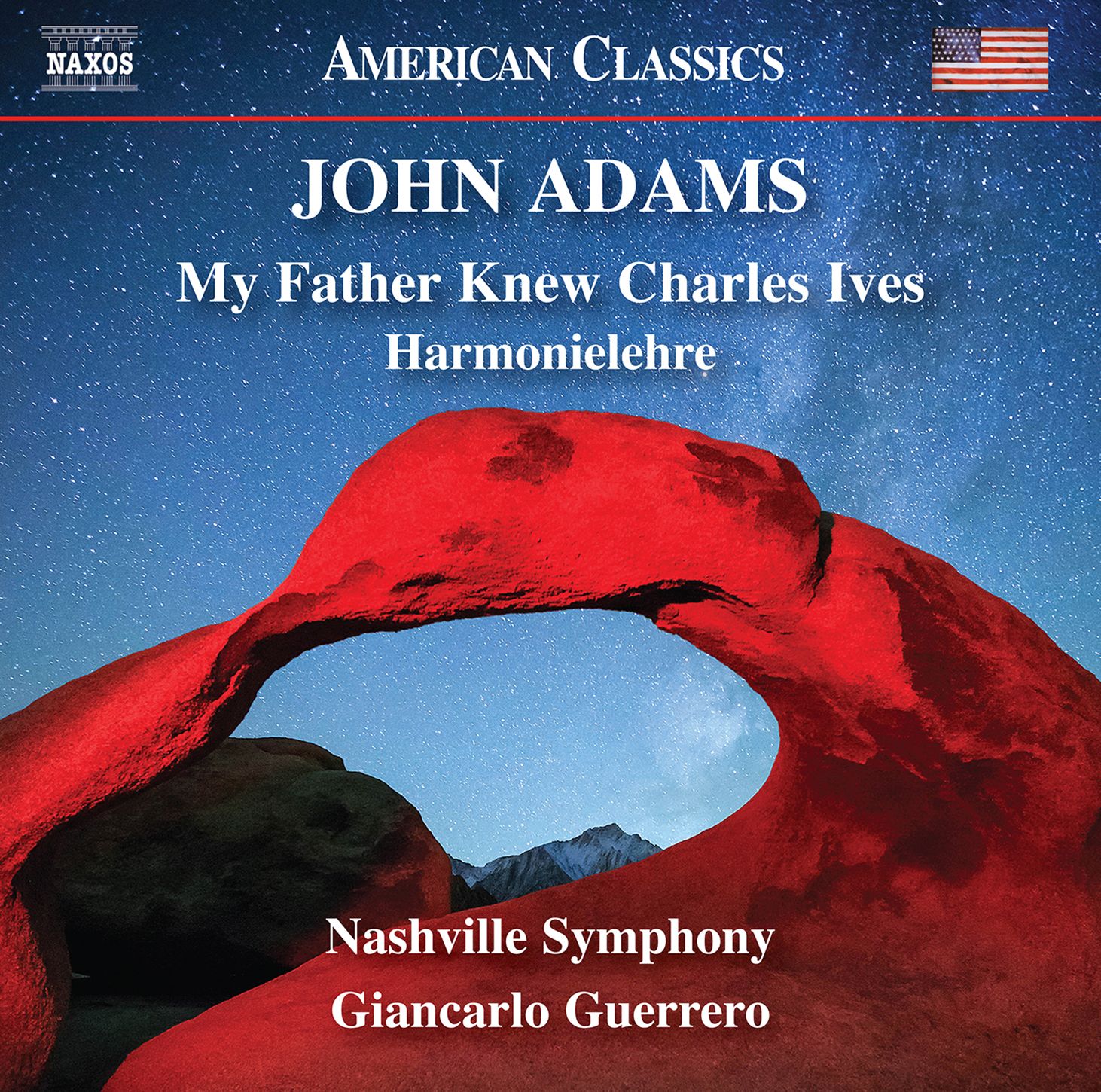

My Father Knew Charles Ives: The Music of John Adams

Those champions of new American music, the Nashville Symphony and Giancarlo Guerrero, turn their attention to the music of John Adams (born 1947; not to be confused with the composer John Luther Adams). Regular readers of Classical Explorer might wish to see this post as a logical extension of our An American Celebration post.

Once upon a time, music theorists were happy to bundle John Adams in among the American minimalists and to mention his name in the same breath as Glass or Reich. But his music is less focusedon minimalism than either; it can be symphonically expansive (as in "The Mountain," the finale of My Father Knew Charles Ives) and traditionally expressive:

Adams describes this piece, written in 2003, as a "homage and encomium to a composer whose influence on me has been huge". Charles Ives (1874-1954) was a one-off, a unique phenomenon perhaps most famous for his layerings of music in different keys: in Ives' music, hymn tunes and popular tunes collide spectacularly. Those very Ivesian parades are here in Adams' homage, too, in the first movement, "Concord" (while Concord, Mass. was associated with Ives, though, Adams is referring to "his" Concord, that in New Hampshire);

The Nashville Symphony and Giancarlo Guerrero offer a spectacular performance, caught in some of Naxos' very best sound. This is only the second available commercial recording of this piece, amazingly (the other is the Nonesuch one under the composer, with teh BBC Symphony Orchestra).

While the disc begins with a tribute to Charles Ives, it continues with a tribute to Arnold Schoenberg in Adams' Harmonielehre (1985). Here, beauty unforgettably makes its presence known. The first movement is 17 minutes long and woorth hearing all the way through. Just immerse yourself:

As Adams points out, there is no sense of "teaching" about this music: it simply represents the culmination of his acivities in that area so far in his life. Fans of minimalism will not be disappointed, particularly in terms ofthe big build-up from 14 minutes in, resulting in a glittering climax.

Directly inspired by Sibelius' Fourth Symphony, the central "The Anfortas Wound" takes us far from the world of minimalism. It also takes us to some scary places. To me, the huge climax remind me of the all-embracing poiwer of the climax of the first movement of Mahler's Tenth:

Adams is a great one for titles (one need just think of Short Ride in a Fast Machine). The finale is called "Meister Eckhardt and Quackie" juxtaposes a 13th-century mystic and the nickname for the composer's daughter, then four moths old and apparenlt making duck-like noises. In a dream, Adams saw the monk carrying his daughter on his shoulders. The lyricism heard earlier melds with emergent minimalism as, as the composer puts it, key centres battle it out ("I simply put the keys in a mixer," said the composer. And may the best key win - it turns out to be E flat major, key of Beethoven's "Eroica" Symphony and the opening of Wagner's Rheingold, the "Vorabend" (Preludial Evening) of the Ring cycle. Here is the complete final movement:

There is no gettting away from the fact that hearing this music live is the best way. From the layerings of My Father Knew Charles Ives to the sweet beautiies of Harmonielehre, there is a real visceral element: as I found out when the New York Philharmonic came to the Barbican in 2017 under Alan Gilbert and gave Harmonielehre (review). We can, today, but hanker after those halcyon, concert-filled days; but instead we have the Nashville Symphony's devoted performances at our very fingertips.

If you want to try out John Adams' music for size, there is no better place to start. And at Naxos' price, it would be rude not to (and, even better, it is slightly reduced at the time of writing, too!).