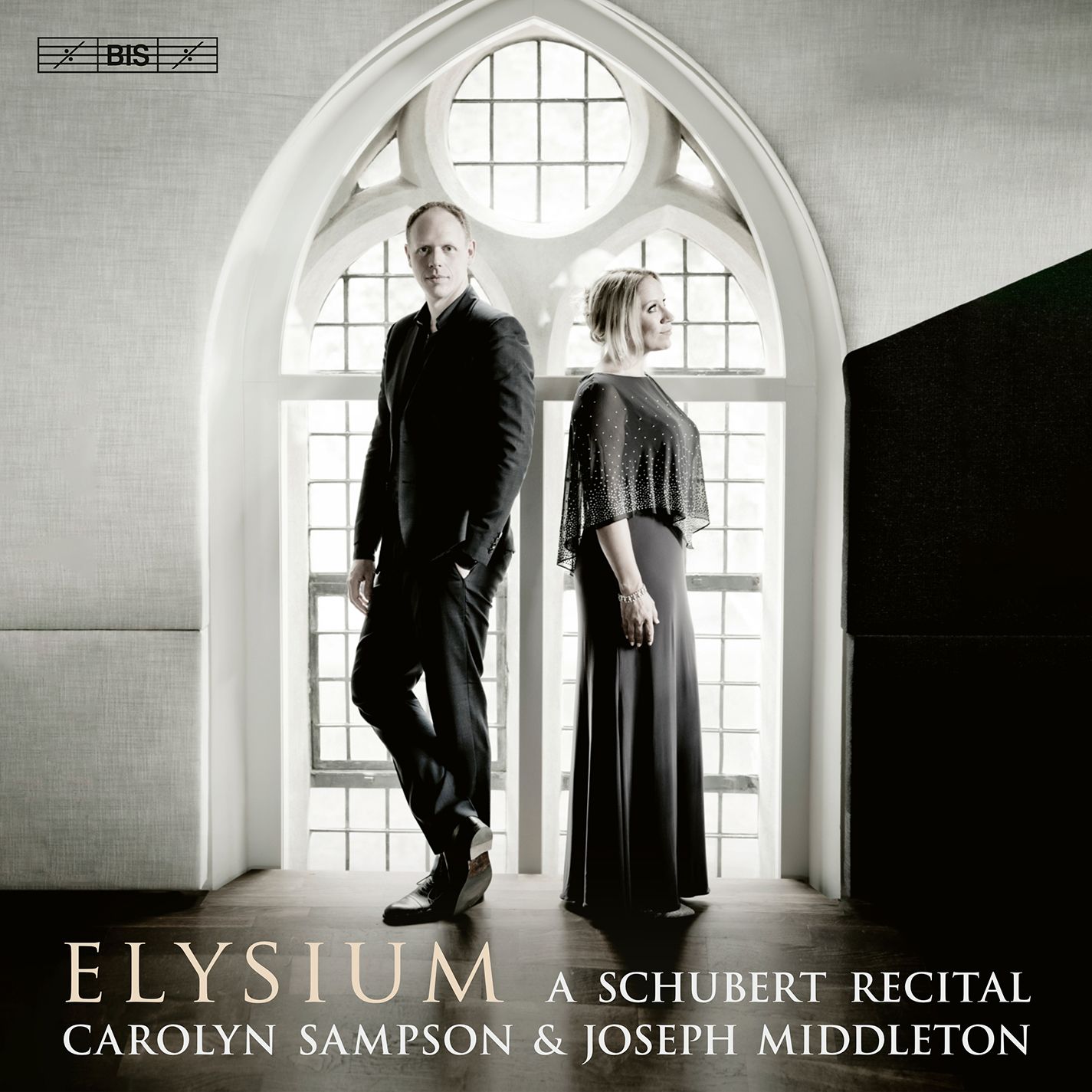

Elysium: Vibrant Schubert Lieder from Carolyn Sampson & Joseph Middleton

This is a beautifully presented, phenomenally programmed and faultlessly performed disc

The theme of Carolyn Sampson and Joseph Middleton’s most recent Schubert disc is Elysium, that elusive place which, as Susan Youens’ superb booklet notes point out, was to some a paradise for dead heroes, or anafterlife for the blessed; for Homer, it was the place of perfect happiness at the end of the flat earth on the banks of the Oceanus (which delimited the outer boundaryof the flat Earth); for Virgil, it was a demarkated place in the Underworld (The Aeneid, Book VI). Schiller refers to “Tochter aus Elysium” in his Ode to Joy (“Freude, Schöner Götterfunken, Tochter aus Elysium”; Joy, beautiful spark of Divinity,

Daughter of Elysium), famously set by Beethoven in the finale of the Ninth Symphony.

We have met, and admoired, Carolyn Sampson before on Classical Explorer: in the post After Dido: Purcell’s King Arthur, again in Purcell in the Birthday Odes for Queen Mary, and in Masaaki Suzuki’s most recent version of the Bach Matthäus-Passion. This is her second volume of Schubert songs for BIS; previously, she released A Soprano’s Schubertiad (BIS-2343).

The song Schwestergruß, D 762 (Sister's Greeting, text Franz von Bruchmann, 1798-1867) has a distinctly eerie story of ghostly flickers, or a figure appearing of noble bent such as one might find in the “lap of God” (Wie in Gottes Schoß). Not one of Schubert’s best-known songs, it deserves to be:

The song Ganymed, D 544, however, is one of Schubert’s best-loved, and most special Lieder. How the purity of Sampson’s soprano reflects the “morning radiance” of the opening lines (Wie in Morgenglanze / Du rings mich anglühst; How your glow envelops me / in the morning radiance). How special, too, Middleton's playing, particularly around the arrival in the text of that echt-Romantic symbol, the nightingale. How wonderfully breathlessly the protagonist’s excitement shows, too, in the approach to the raidant staement of “Allliebende Vater”’ (yes, it”s got three 'l's in it, as has English but we insert a hyphen: all-loving Father):

Sampson and Middleton’s approach is necessarily different from that of Jessye Norman’s famous reading with Phillip Moll - Jessye is less Spring-fresh, perhaps than Sampson/Middleton, but what a satisfying arrival Norman and Moll provide at the end (YouTube video).

The song An den Mond, D 259, begins in complete contrast, Middleton shading the piano part perfectly; and how he emphasises the narmonic 'stab' in the cadence after the first stanza before Shcubert lightens the tone considerably for “Enthülle dich, dass ich die Stätte finde” (Unveil yourself, that I mai find the spot [where my beloved sat]).

Middleton’s lightness is once more in evidence in the famous Auf dem Wasser zu singen, D 774, a barcarolle for gliding through life towards eternity (the text was written by Friedrich Leopold, Graf zu Solberg-Stolberg, 1750-1819, on falling seriously ill during his honeymoon). With Sampson’s sure sense of line, her perfect projection of the song’s bitter-sweet persona. Die junge Nonne, D 828,is another famous song, but rarely has it been captured with such an undercurrent of seething disquiet as here, an energy which periodically surfaces, thrillingly. The tolling of the bell for the dead is heard intehpiano as the songer intones “Allelujah,” so poignantly. Both are perfectly judged here:

.

The song Gott im Frühlinge (text Johann Peter Uz, 1729-96), D 448, was new to me. It is less than two minutes in duration, but what a two minutes!. A song of appreciation of Nature, the piano’s final cadence is a master-stroke of surprise, here something of the equivalent of a cross between a semi-colon and a full stop:

The voice’s entrance in Nacht und Träume, D 827 (Matthäus von Collin, 1779-1824) is one of the glories of the entire song repertoire, and Sampson does not disaapoint; neither does Middleton, when it comes to honouring Schubert’s harmonic shifts:

How glorious the piano/voice dialogue in Die Sterne, D 939, an inspired song that deserves to be far better known, a homage to stars and a rumination upon their multiple functions. Listen to how Middleton varies Schubert's omnipresent dactylic rhythms, too:

A memorial to a suicide (Christel von Laßberg, who drowned herself, with a copy of Goethe’s Werther in her pocket, in a spot close to the author's own house), An den Mond, D 259 is a touching song in that disarming and misleadingly simple mode used by Schubert. There are huge layers to this song, if one takes the time to listen. The song Litanei auf das Fest Allerseelen, D 343, to a text by Johann Georg Jacobi (1740-1814), wears its profundity for all to hear. How tenderly Middleton delivers Schubert’s seemingly simple part; how softly Sampson spins the melodic line:

An die Nachtigall, D 497 is a short but phenomenal song - as booklet annotator Susan Youens points out in her superb notes, this song is replete with subtleties; and how contrasting is the well-known Der Musensohn, D 764 - but has the piano part ever frolicked like this? Middleton is surely Schubert's invocation ofthe irrepressible energy of a Spring lamb:

The discovery of Schubert songs as one goes through life is one of the great joys. So it is, for me, with Die liebliche Stern, D 861 (text Ernst Schulze, 1789-1817), probably the sweetest setting of a death wish in existence (the song depicts Nature ignoring the poet's aching heart):

The ensuing Wiegenlied, D 867 (Cradle Song, text Johann Gabriel Seidl, 1804-75) offers a gentle response as the poet links temporary sleep to the longer one of death. Schubert’s setting honours the quasi-hypnotic strophic openings “Wie ...” (how ....) in true cradle song manner:

... and it is genius to follow this with the concentrated, held-breath Du bist die Ruh’, D 776, its approach to the climactic “Allen erhellt” perfectly judged. The concentration in this performance is surely that of a live performance, with stilled audience:

Schubert’s own song Elysium, D 584, is remarkable for its haronic breadth and, in this performance, for Middleton’s lightest of touch at speed and Sampson”s projection of impetuosity. And what a backbone the song reveals for itself:

The recital ends with a melodrama (spoken text with piano). This piece was untitled, but is now known as Abschied von der Erde (Farewell to the Earth; trhe texr is by Adolf von Pratobevera, 1806-75). Schubert’s piece is truly beautiful: there is something unbearably poignant about a spoken “Leb' wohl” (Farewell) against Schubert’s beautiful piano writing:

This is a superbly presented, phenomenally programmed and faultlessly performed disc, complemented by incredibly informative and informed booklet notes by Youens (author of two Cambridge University Press books: Schubert's Late Lieder: Beyond the Song Cycles, 2002, and Heine and the Lied, 2007).

Full listing of songs:

Schwestergruß, D 762; Ganymed, D 544; An den Mond, D 193; Auf dem Wasser zu singen, D 774; Die junge Nonne, D 828; Gott im Frühlinge, D 448; Nacht und Träume, D 827; Die Sterne, D 939; An den Mond, D 259; Litanei auf das Fest Allerseelen, D 343; An die Nachtigall, D 497; Der Musensohn, D 764; Der liebliche Stern, D 861; Wiegenlied, D 867; Du bist die Ruh, D 776; Elysium, D 584; Abschied von der Erde, D 829