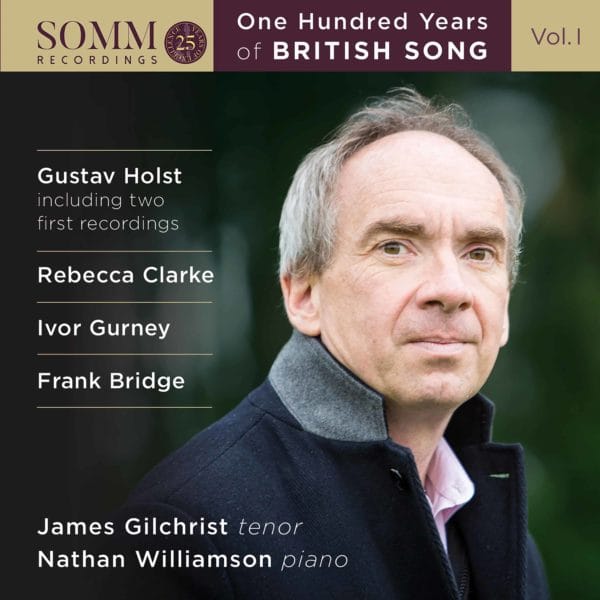

One Hundred Years of British Song, Volume 1

This is an absolute treasure trove of British song in the hands of one of today's most sensitive and intelligent singers: tenor James Gilchrist. joined but he superb Nathan Williamson on piano.

This is the first of a projected set of three volume of British song: the first two volumes present composers around the two World Wars; the third, ones from 1960 onwards.

It is amazing to think that Holst wrote 98 songs, most of which are still unpublished. The disc in fact begins with a World Premiere recording, A Vigil of Pentecost, H 123, to a text by Alice A. Buckton (1867-1944). It might feel familiar, though, as it opens with what is surely a sketch for “Venus” from The Planets. Those familiar harmonies just glow, and hearing them on piano reveals Tham in their barest ones. As Nathan Williamson points out in his fantastically informed notes (worth the price of the album alone!), whereas in orchestral garner's there is nary a fun cadence anywhere, here, Holst doe punctuate the piece with clearly tonal cadences. The poem itself is a masterpiece of spiritual verse (it actually shies away from overt Christianity):

If A Vigil of Pentecost maps onto The Planets, The Battle of Hunting Knowe (H 147, text E. A. Ramsden, set in the 1920) aligns with Holst's St Paul's Suite (1913). Another first recording, the let's references to a ghostly horse-borne hunter chasing the protagonist puts me in mind of Schubert's Erlkönig. Hunting Knowe ias a place in teh Scottish Borders (“A ghost rode over Hunting Knowe / With a maiden in his arms” says the text). Another first recording, Holst's score presents the idea of motion, and of mystery all in his own individual vernacular:

Holst's Op. 47 (H 174) is a set of Twelve Humbert Wolfe Songs to text by that poet (1885-1940). These dozen songs were not intended as a cycle but were collated for publication in 1969 in an oeder chosen by Britten and Pears (who went on to record them).

Williamson points out that Imogen Holst referred to Op. 47 as “possibly the turning-point in the journey towards the warmth of the misc [Holst] wrote at the end of his life”. Certainly, “Persephone,” the first heard here, as a swirling piano part that takes us to different worlds, with the haunting vocal line above urgent the return of the titular character:

It has to be said the vocal line, when one hears it, seems perfect for Peter Pears, and indeed it is. The Pears/Britten recording is swifter than Gilchrist/Williamson, more urgent. Both views, as you will hear, are equally valid:

I love “A.Little Music”: elusive, yet playful. “Since it is evening / Let us invent / Love’s undiscovered continent” begins the text. The fantastical text seems perfectly reflected in Holst's response, the fluid piano part the perfect creator of this almost fairytale landscape:

In a song that strikes me as about enchantment, I find Gilchrist and Williamson more evocative and atmospheric than Pears and Britten (YouTube link). I find Philip Langridge on Naxos, with Steuart Bedford on piano, closer to teh Some recording, and that disc offers all 12 songs:

The song “The Dream-City” seems to take us into even headier climes, harmonically. its chords floating as the poet invents newly-build society (perfectly apt in foreshadowing the post-1945 post-war spirit. This is all done quietly, with a sense of, in Gilchrist and Williamson's recording, hushed wonder:

The song “The Floral Bandit” is interesting as it parodies Schubert and Purcell (the latter absolutely deliciously, especuially as heard with Williamson's perfect staccato touch). while remaining Holstian to its core:

The final excerpt here, “Betelgeuse,” reminds us of Holst's astronomical predilections, and he presents, via Wolfe’s stunning verse, a portrait of an idyllic, “golden” space; more enchantment, perhaps! Certainly the words “golden” and “gold” return severally, perhaps quasi-hynotcally:

We've met composer Rebecca Clarke a couple of times on Classical Explorer: her Prelude, Allegro & Pastorale on Metier, and her Ave Maria as part of Pembroke College Choirs' Signum disc, all things are quite silent. Now it is teh turn of a sequence of four songs (she composed over 50 works for voice, with a variety of instruments). The clutch of four songs Gilchrist and Williamson present have this listener at least aching for more. You can read a rather nice overview of Clarke's output in this article from the Oxford International Song Festival's website.

First, June Twilight, a 1925 setting of Masefield, its vocal line entering on the low end of the tenor register (Gilchrist is undaunted). If anything, there is even greater profundity here than in the Holst - praise indeed!

More Masefield, but in a different vein, in The Seal Man. While June Twilight is nicely strophic, The Seal Man (1921/22) is more of a prose poem, and Clarke's response is astonishing in its unbridled invention. This link (to a page at the Rebecca Clarke website) offers further information about the song. Clarke's response is at once unpredictable and yet perfectly cogent in terms of her musical voice:

This is not James Gilchrist's only recording of this song: there is a version with pianist Simon Lepper for King's College Cambridge, and that is a somewhat more urgent take (it is faster: 5’28 as opposed to 5’58 - but it also has more underlying tension). Both views work well, perhaps a testament to the strength fo Clarke's writing:

Rebecca Clarke hardly shies away from setting the greats in poetry. From Masefield, we move to W. B. Yeats for A Dream, an evocative setting, its unaccompanied solo lines implying loneliness, even discombobulation, an atmosphere only lightened by a memory: “She was more beautiful than my first love, / This lady by the trees”:

.. and from Yeats to A. E. Hausman for Eight O'Clock, the piano's repeated chords invoking the striking of the hour from a such steeple. Only a few seconds over two minutes, this song is like a miniature tone-poem. The piano's dissonances are notable:

From Rebecca Clarke to Ivor Gurney (1890-1937). Although known as a war composer, both Snow and Sleep were written pre-war. Down by the Salley Gardens is one of his more famous songs and readers might already be aware of performances by the likes of Anthony Rolfe Johnson and Ian Partridge. Gilchrist and Williamson present it beautifully:

The sense of harmonies suspended in time in Snow (text Edward Thomas) is palpable. As Williamson says in his notes, this is, along with Sleep (also included here) one of Gurney's most powerful songs:

An alternative, female voice to Snow is found in this remarkable performance by Susan Bickley and Iain Burnside on Naxos. It really is the perfect complement to Gilchrist and Williamson; Bickley remains one of the most compelling artists around today (my report on her performance as Judith in Bartók's Duke Bluebeard's Castle in Beijing last November appeared in the most recent edition of Opera Now, January 2024):

Gurney sets more Thomas in Lights Out, replete with haunting harmonies that seem to circle, menacingly. “I have come to the borders of sleep,” says the text. It is to John Fletcher that Gurney turned for the last of this set, though, in Sleep (from Five Elizabethan Songs), its text naturally complementing that of Thomas' words, some 200 years later. It works terrifically well to hear them one after the other, and just listen to the harmonic complexities of the latter:

There is no shortage of truly great poetry on this disc. Frank Bridge set words by Rabindranath Tagore and Humbert Wolfe for the four songs we hear from 1925. The modernity of the first of the Three Songs of Rabindranath Tagore, H 164, “Day after Day” might come as a surprise. textures are thinned down, lines angular, harmonies poignantly pungent:

The second, “Speak to me, my love!” is a held breath song. with Gilchrist and Williamson perfect in their pacing and atmospherics. The final song is “Dweller in deathless dreams,” and it strikes me that Bridge's harmonic mastery reaches its peak here. His response to Tagore's text is often meltingly beautiful:

Finally, for the set of four Bridge songs, a that setting of Humber Wolfe's Journey's End, Could there be a more fitting final song for this disc? Although bracketed together with the Tagore setting as "Four Songs" on the Somm disc and published as such by Stainer & Bell, it is a separate piece in Imogen Holst's catalogue of her father's works, with its own catalogue number (H 167). Bridge wrote it for “tenor or high baritone” and it casts a lasting spell:

Nathan Williamson plays on a Fazioli piano,a make known for its clarity of sound; yet Williamson finds warmth there, too. It feels like the perfect choice for both pianist and composers.

A fascinating disc, invaluable for the Holst recorded premieres, yet a superb hour's-plus worth of listening in its own right.

This disc my be purchased at Amazon via this link.