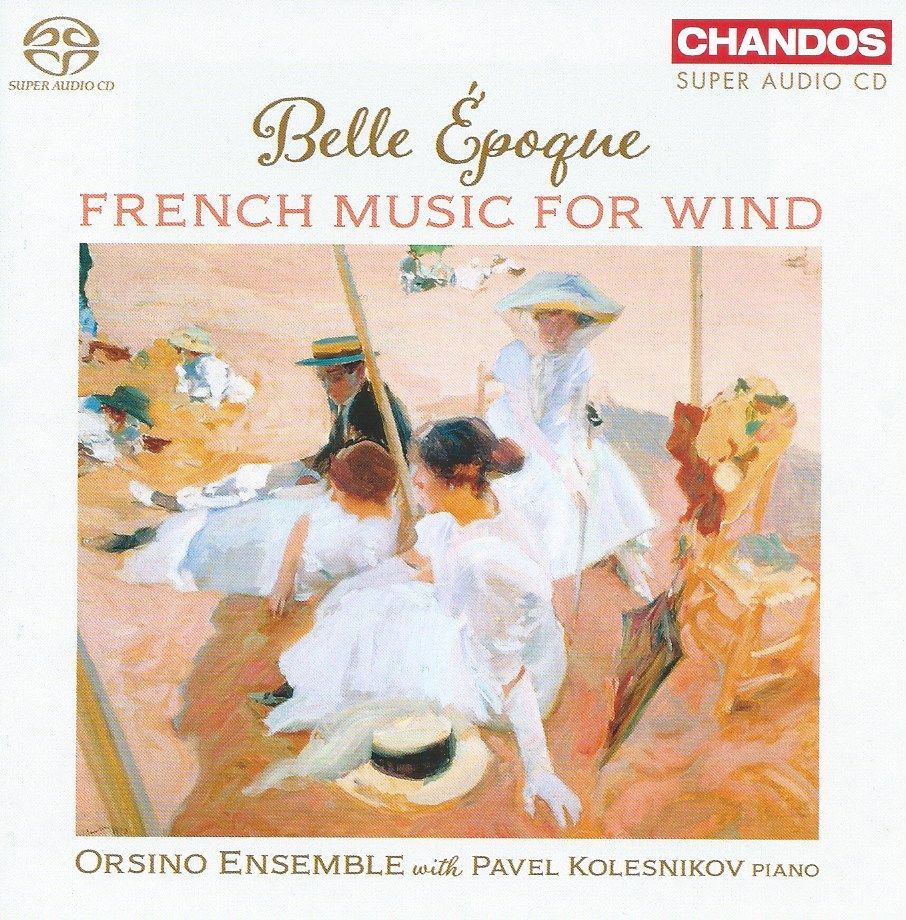

Belle Époque: French Music for Wind

A selection of delicious French music from the so-called "Belle Époque" ...

The last two posts this week have been, it is fair to say, about operas that carry their fair share of drama, from exploitation and death in Mascagni's Iris to a pact with the Devil in Gounod's Faust. Both result in an explosion of powerful, often beautiful music, but maybe it's time for an interlude.

And here on Chandos, released today, is a selection of delicious French music from the so-called "Belle Époque," that period from around 1880 and 1914. In Paris, particularly, the artistic world was preternaturally alive, and the six composers we have here - Albert Roussel, Achille-Claude Debussy, Camille Saint-Saëns, Charles Koechlin and André Caplet - were all active at that time. And the music we have here is performed by "Orisino Ensemble," a collection of some of the finest wind players around today: Adam Walker, flute; Nicholas Daniel, oboe; Matthew Hunt, clarinet; Amy Harman, bassoon; and Alex Frank-Gemmill, horn, itself joined by that most thought-provoking of pianists, Pavel Kolesnikov.

Everybody needs some Albert Roussel in their lives. His music, I mean - beautifully constructed, vibrant, alive. I first got to know his output many years ago via an unexpected source: Herbert von Karajan in a recording of the Fourth Symphony with the Philharmonia Orchestra. Old habits run deep. Let's hear the finale as a sample:

Certainly Roussel's Op. 8 Divertissement ticks all the boxes of charm, superb constriction and scoring (flute, oboe, clarinet, bassoon, horn and piano), and the performance here is stunning:

Debussy's Première Rhapsodie for clarinet and piano is one of his best known pieces (there was to be no Deuxième Rhapsodie, sadly). It makes huge demands on the performer, and Matthew Hunt and Pavel Kolesnikov reveal the utmost sensitivity. to the score while making light of the demands. They weave a magical web, Hunt's legato a joy.

Saint-Saëns' Romance for horn and piano, Op. 36 (1874) is a dream, as one might expect from this composer. One lives and learns - having played this piece in its horn aspect, it turns out it is actually a transcription of a movement from a Suite for cello and piano of some 12 years earlier. Alec Frank-Gemmill is one of the finest players in front of the public today, and he plays the piece with superb legato. The climax is finely judged, exciting but not overblown; the fragmentary gestures before the return oft he opening are magnificently quizzical.

I've said it before and I'll say it again, Saint-Saëns, despite his fame for Carnaval des animaux etc, is one of the most under-rated composers out there. Lovely to have the little-known Caprice sur des airs danois et russes, Op. 79 (1887). Dedicated to the Russian Empress (Tsarina) Maria Fedorovna - who was Danish by birth hence the two nationalities of the source materials. It is light, frothy, and perfect; and the piano and tutti flourishes with which it opens is superbly done here:

Cécile Chaminade is represented by a competition piece, the Concertino for flute and piano of 1902. Chaminade's florid lines are atmospherically delivered by Adam Walker. Chaminade's music has a grace to it: Roger Nichols in his excellent notes is right to make parallels with Mendelssohn here:

Charles Koechlin (1867-1950) has, if anything, an even more elusive harmonic world than the other composers here. His rarely-heard Nocturnes, Op. 32bis are for the unusual combination of horn, flute and piano (listed in that order!). They were not published until 1989 and exhibit a tendency to push the envelope a little further in terms of dissonance:

Caplet's Quintet, Op. 8 bursts with invention throughout its nearly half-hour duration. Certainly the Adagio slow movement expands out beautifully; the finale has a lovely outdoorsy quality to it.

There are two very brief pieces by Debussy here: a short sight-reading piece for a clarinet competition in 1910 (Petite Pièce) and the famous, seminal Syrinx. The clarinet one is over before you know it, but remains utterly charming; Syrinx, however, is a piece of massive import, influencing composers such as Pierre Boulez and Edgard Varèse. Elusive, as Nichols points out it has points of contact with the equally epoch-making Debussy ballet, Jeux. What a way to end!: as you can hear, Adam Walker is simply superb: