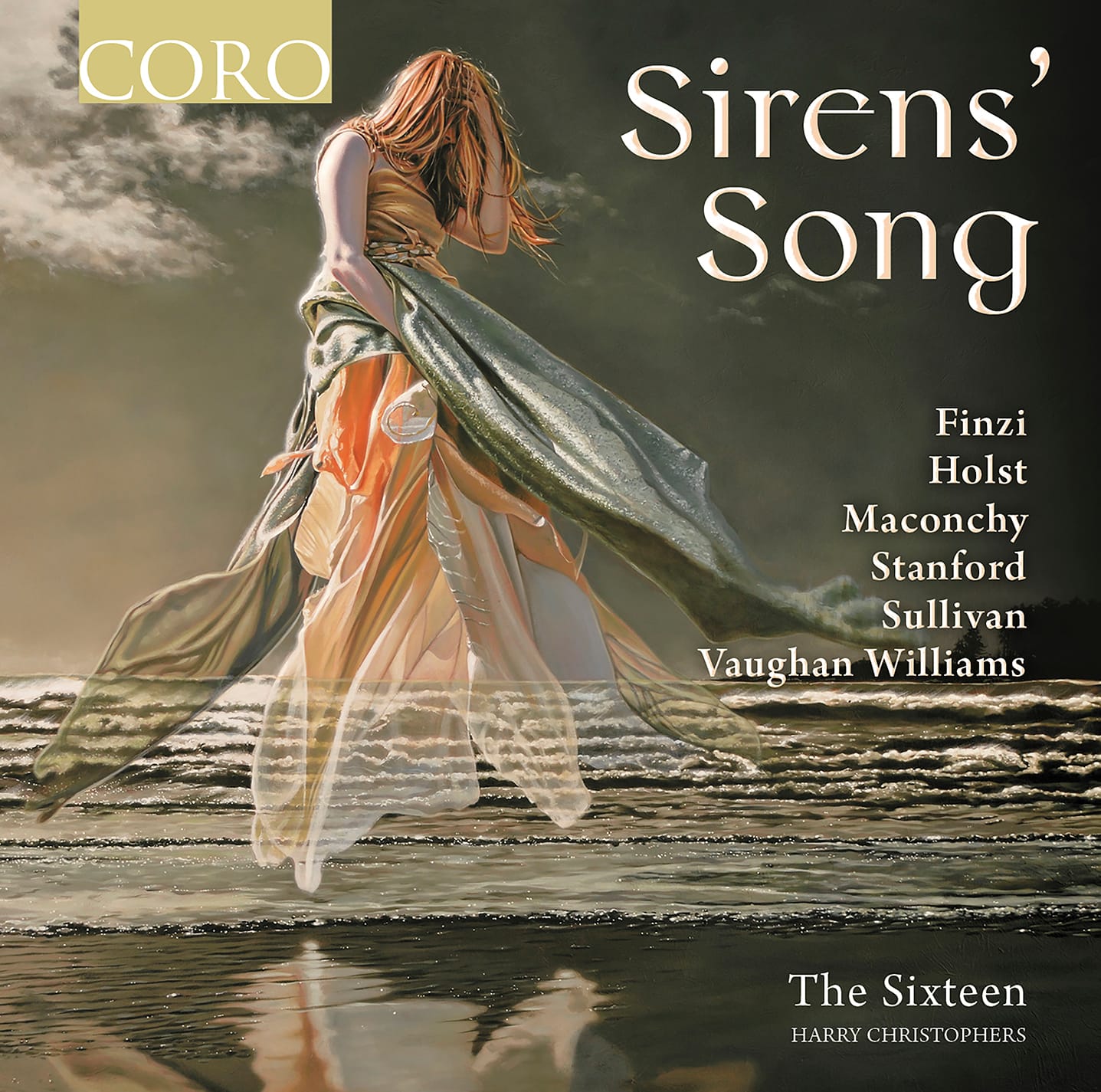

Sirens’ Song: The Sixteen in English Partsongs

What's not to like? This is choral music, and choral performance, at its very best

While The Sixteen is known for its performances and recordings of sacred music, here they offer a whole disc of secular songs, of English gems, including Stanford's Eight Partsongs. The emphasis is on the pairing of music and poetry: that Stanford group is based on the poetry of Mary Elizabeth Coleridge, for example, while Imogen Holst’s six offerings set John Keats, and Finzi offers Seven Poems of Robert Bridges.

“What would singing be without words?" asks Harry Christophers in an introductory note; and indeed , the poems of Mary Elizabeth Coleridge (1861-1907: she died prematurely, of appendicitis), set by Stanford in his Eight Partsongs, Op. 119, find music and poetry deliciously hand-in-hand. Our second visit to the music of Stanford in one week! So the first song, "The Witch," is a perfect fusion of story-telling and harmonic balance. Stanford shades the drama superbly (rising the stakes at “The cutting wind is a cruel blow”):

The truth is that The Sixteen are as exceptional in secular music as in sacred. The generally melodically-driven music (as opposed to the counterpoint of the church) has its own clear appeal. Stanford writes clear-cut lines, memorable melodies, shot through with beauty, as in the second song, “Farewell, my joy,” the poem's valediction:

The next song from Op. 119 is the most famous, "The Blue Bird". Stanford seems to set the poem reflecting not just the idea but the particular shade of colour: “A bird whose wings were palest blue”; and as the colour ripens (as the attention moves to the sky), so the harmonies become that touch richer. You can hear The Sixteen's Sirens' Song at Spotify; I just thought this live excerpt from Perth might be interesting:

The fourth song, “The Train,” was new to me and is active, propelling its way towards the ecstatic, almost mystical setting of Coleridge's memorable line “Where are you, Time and Space?” moving to the equally remarkable conclusion, almost Parsifal like in philosophy, that “You are one”:

The Partsongs offer a variegated tapestry; Coleridge's remarkable poem “The Inkbottle” is set in jaunty fashion, while Stanford's melodic lines surely mimic the flight of the titular bird of No. 6, “The Swallow”:

Of all the Partsongs by Stanford in this set, the most pure, ad the most purely beautiful, is “My hand in thine,” the final offering. Somewhat hymnic, it is the suspension on the word "thine" that gets me every time:

A single song separates the sets by Stanford and Imogen Holst: Elizabeth Maconchy's remarkable Sirens' Song, from which the disc takes its name. Wordless initially, Maconchy goes on to set words by William Browne (1591-c. 1643). Julie Cooper is the pure-voiced soprano soloist. This is a major piece; Harry Christophers writes that he has ...

... been fascinated by the music of Elizabeth Maconchy for many years; I remember playing the clarinet in one of the early performances often children's opera “King of the Golden River” and, when sifting through the music, I came across “Sirens' Song’. On the page it looked dreamy yet evocatively luring and, unsurprisingly, it did not disappoint.

Then on to Imogen Holst's extended Welcome Joy and Welcome Sorrow for females voices and harp, in which the composer sets Keats. This is a set of six partsongs, the first having a Britten-ish tinge, to my ears, before twisting inwards harmonically, the harp (Sioned Williams, Principal Harp of the BBC Symphony Orchestra, does the honours):

The harp sparkles and scintillates in the third song, “One the Hill and over the Dale”:

.. which sits in high contrast to the next partsong, “O Sorrow,” with its absolutely delicious yet aching high-voice dissonances. The control and purity often sopranos is astonishing here:

A gently-rocking lullaby seems innocent enough until the voices enter, almost a prolongation of Maconchy's sirens. This is a remarkable song, proof positive of Imogen Holst's stature as a composer. Starlight and moonlight illuminate the texts soft imperatives of “Listen, listen, listen, listen ...”:

After that, the final song, “Shed no Tear,” seems like a prolongation. It is of course a composed leave-taking, and effortlessly set by Imogen Holst.

Just one partsong by Ralph Vaughan Williams appears, and all the more cherishable for its singleton status: Silence and Music, to a poem by the long-lived Ursula Wood (1911-2007). This was part of a set of commissioned works for Queen Elizabeth II's coronation (A Garland for the Queen); small wonder the cries of “Rejoice” are shot through with light:

I have often celebrated the music of Gerald Finzi. How wonderful to have a cycle of partsongs here, Seven Poems of Robert Bridges. Bridges (1844-1913). Finzi seems to relish every syllable of Bridges' poetry - as in the second song, “I have loved flowers that fade”:

There is some exultant counterpoint (briefly, but repeated) in “My Spirit Sang All Day”; what a lovely partsong this is, and how shaded the performance. The Sixteen clearly relish every word:

On a performance level, perhaps the finest on this disc is that of the fourth partsong of the Finzi cycle, “Clear and gentle stream,” a celebration of the combination of Finzi's perfect reflection of Bridges' words:

It takes a group like The Sixteen to bring off “Haste on, my joys!” properly. The music's core effervescence requires choral virtuosity, not to mention brave sopranos. This is a splendid performance; the final “Wherefore to-night so full of care” emerges as so much balm:

It is left to Sir Arthur Sullivan, though, to close the programme, setting Henry Fothergill Chorley (1808-72) in The Long Day Closes. One of a set of seven partsongs, this is heard in its later setting for mixed voices (the original was for male voices). The texts funerary bent meant that the piece was often sung at the funeral of members of the D'Oyly Cate Opera Company:

The recording is perfect from all angles. Set in the lovely All Hallows' Church, Gospel Oak, the experiences Mike Hatch is engineer, while Mark Brown oversees all as Producer. Full texts included, booklet essay and that introductory note from Harry Christopers himself. What's not to like? This is choral music, and choral performance, at its very best.

The disc is available from Amazon here; Spotify below.