Nightlight: Cordelia William's beautifully themed recital

Here, Mozart, Scriabin, Liszt, Schubert, Thomas Tomkins and Bill Evans all rub shoulders, culminating in - joy of joys! - Schumann's Gesänge der Frühe, Op. 133, the exquisite fruit of that composer's troubled late period

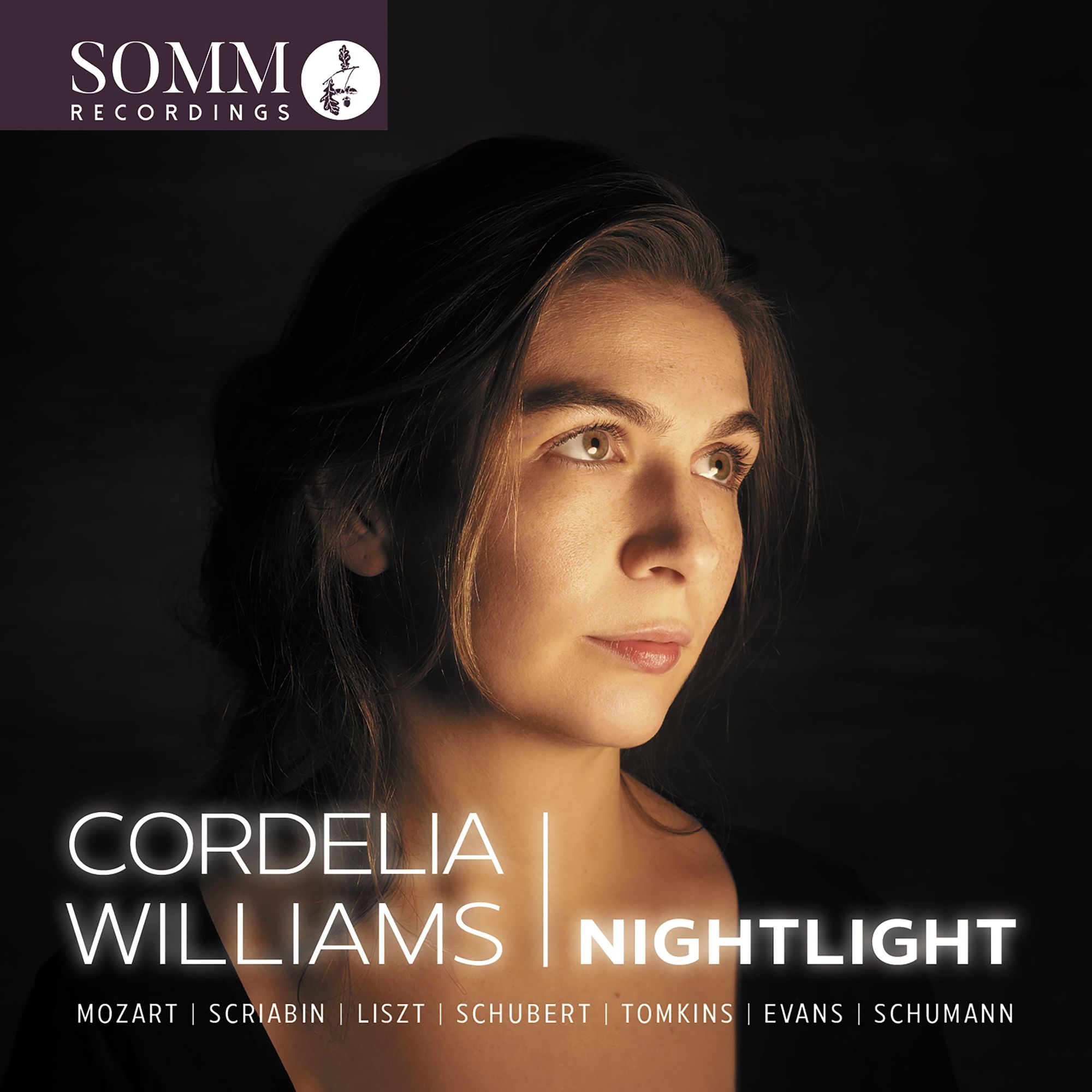

Cordelia Williams is clearly a lady who likes fascinating juxtapositions of pieces (think of her Bach and Pärt album) and who enjoys exploring the gold hidden in the corners of the piano's repertoire. She seems to hit gold on both fronts on her most recent disc, Nightlight, released on August 20, 2021 on Somm Recordings. Here, Mozart, Scriabin, Liszt, Schubert, Thomas Tomkins and Bill Evans all rub shoulders, culminating in - joy of joys! - Schumann's Gesänge der Frühe, Op. 133, the exquisite fruit of that composer's troubled late period.

But there's a whole programme before that. Here's the promo video for this disc:

Let's start at the beginning though. The disc is "dedicated to people who, for whatever reason, feel alone in the darkness," says Williams. The concept centres on the Dark Night of the Soul - of "leaving behind the self on a journey towards illumination and spiritual wholeness". For Williams, there is an analogy for moving from "pianist" to "mother"; there are certainly polarities to be found in both activities.

Heard in this way, Mozart's stunning Fantasia in D minor seems to hit bull's eye, its exploration of the dark finding occasional but soul-searchingly beautiful moments of major-key illumination.

Scriabin's "Sonata-Fantasy." his Piano Sonata No. 2, was inspired by that composer's experiences of the sea. Williams captures all of the elemental power of the first movement Andante; her finger dexterity in the Presto finale (there are two movements) is remarkable, as is the way she allows each detail to speak while capturing the exquisite curlicues - like the rising smoke trail of an incense:

Liszt's heavenly musings, of course, have a place here. Two of the Consolations, again a Gemini-like pairing, complementary twins like the movements of the Scriabin: both in E major, Liszt's offerings present a bed of sound.

It is left to Schubert to rouse us with the rock-hewn opening of the C minor Sonata, D 958, the first of the last great three Sonatas that culminates in the expansiveness of the B flat Sonata, D 960. Eschewing the nightmare passages of D959, Williams has opted instead for the contrasts and confrontations of the C-Minor; and how the rumbling bass opens the door to a darkness of the mind here.

This is fine, even great, Schubert playing, the transformation of the calm of the opening of the Adagio, exquisitely presented, to somewhere altogether darker in the psyche is a properly disturbing one. Accents like death knells destabilise, disorient us so that when we hear the opening again everything has changed; its innocence is lost. This is not a sonata that finds peace, not in the shifting Menuetto, nor in the finale, its dotted theme nervous, unable to find stillness. Here's that slow movement:

It is perhaps surprising to find some Thomas Tomkins here. It is a piece that could be titled for today: A Sad Pavan for Distracted Times. It really is good to hear Elizabethan keyboard music find adherents on the piano: Kit Armstrong has recently recorded William Byrd and John Bull on DG, the perfect next stop of, like me, you find Williams' performance of the Tomkins deeply affecting in its emotional honesty.

Bill Evans might seem an unlikely follow-on but his Peace Piece, a post-Chopin Berceuse, somehow seems completely inevitable. It is perfectly realised here by Williams, the lazy right-hand melody singing over that quietly rocking left hand.

But then, the true treat of the disc. Schumann's Gesänge der Frühe (Songs of the Dawn) dates from October 1853 (he died in 1856). Harmonically enigmatic in that particular way only Schumann knew how to conjure. There are intimations of late Brahms here, certainly (I hear them particularly strongly in the second piece) while what are surely fanfares dominate the third.

Here's the fourth, "Bewegt," swirling music that could be of dawn or dusk, perhaps. certainly the point seems to be, in this Scriabinesque milieu, it is the liminal state that is important:

Relief comes with that dawn, in the fifth and final piece, radiantly chordal before slowly uncoiling itself. It is not, perhaps, inappropriate to refer to Schumann's Op. 133 as one of his greatest pieces of piano music; and Cordelia Williams' performance is exquisite. Here's that last piece: