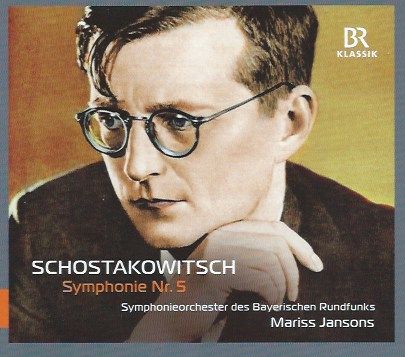

Mariss Jansons' live Shostakovich 5

The passing of Latvian conductor Mariss Jansons in Saint Petersburg in November 2019 was a huge loss for the music world. His father, Arvīds Jansons (more often known to the musical public as Arvid Jansons) was a fine and respected conductor himself, who regularly conducted Manchester's Hallé Orchestra. But it was Mariss who was associated with the World's greatest orchestras, most famously the Royal Concertgebouw Orchestra, which he took over after the departure of Riccardo Chailly. Jansons also acquired a reputation as an orchestra trainer, honing the ensembles he fronted to their best: his tenure with the Oslo Philharmomic and the famous Tchaikovsky recordings on Chandos that resulted are testament to this.

This is not Mariss Janson's first Shostakovich Fifth. His multi-orchestra "official" Shostakovich symphony cycle found him in front of the Vienna Philharmonic for the Fifth; interesting that here we have the Bavarian Radio Symphony Orchestra (Symphonieorchester des Bayerischen Rundfunks), like the Vienna Philharmonic not known for its love of brazen sounds. In fact if anything the core Bavarian sound is even lusher and just as unforgettable (a Mahler First Symphony under Rafael Kubelík in Manchester in the early 1980s, plus subsequent live revistings over the years, confirms their sound remains as fine as ever). And yet, Jansons ensures we come away both energised and disturbed: the mixed messages of the Fifth Symphony itself are laid bare. Popular the Fifth Symphony may be; easy listening it most certainly is not.

This live Fifth was recorded over several dates (so therefore there will have been some switching between performances) in April/May 2014; the immediate audience cheers after the "triumphalism" (or is it?) of the finale are enthusiastic and immediate - and deserved. In the old LP days, Decca had a recording technique it called "ffrr": full frequency range recording. You could say the same of Janson's approach a full frequency range performance, from awe-inspiring fortissimos to the quietest of pianissimos, with the Bavarian recording allowing it all to shine through (your neighbours might enjoy the louder passages along with you). You can hear both dynamic extremes in the first movement:

Here, the intensity of the extended Moderato introduction cedes to an Allegro non troppo that certainly moves: Janson's interpretation fo "non troppo" is such that it can still be fast as long as we hear everything. And indeed, detail is magnificent; but so is Janson's rhythmic control, which allows for properly cumulative climaxes.

Oh how Shostakovich's use of the indication "Allegretto" can be misleading!. In the general run of things, it tends to indicate a certain lightness: easier to hear jackboots in Shostakovich's movement, even if Jansons comes across as just a little soft in comparison with some of the decidedly raw Russian performances out there:

The Largo is one of those expansive Shostakovich slow movements that seem to stretch on forever. It's easy to lose oneself in the process, and such was surely the intent: a frozen wasteland that rises to a crushing climax. Jansons takes just under a quarter of an hour (13"01), laying bare a sense of desolation couched in the utmost sonic beauty:

After that, the finale explodes on the sound stage like a blazing comet:

Its message is ambiguous, though. This might have clear D major, the home key, all over it, particularly at the end, but is all what it seems? After the Fourth Symphony, a magnificent, monumental work in which two huge modernist movements frame a slip of a Scherzo, and the controversy it raised, Shostakovich's Fifth Symphony was ostensibly, in the composer's own words, "a Soviet artist's creative response to just criticism"; and, in the controversial book Testimony, Shostakovich reportedly talks about a "forced rejoicing". Certainly the emphasis on the arrival of the home D major is extended - some might claim deliberately distended. The irony is that it never fails to stir an audience - as we can hear in this case.

Some readers will have a shelf-full of Shostakovich Fives already (or several flash drives, these days); others might be coming to the score for the first time. This Bavarian reading would be a fine introduction, the score beautifully clearly laid out and realised. Other responses to the score - Bernstein, Rostropovich, Mravinsky, Kondrashin, Sanderling - offer other experiences, each individual, each gripping, each worthy of investigation for the more explorative listener.