Kammerkonzert: Music of Arnold Schoenberg from Odradek

Schoenberg's music requires concentration from the listener, but the rewards are massive

Arnold Schoenberg”s Piano Concerto (1942) is often thought of as a hard nut to crack. Brendel famously recorded it on LP, and Mitsuko Uchida has made a fine recording more recently. Here we have an arrangement for 15 solo instruments (balancing the Chamber Symphony at the other end of the disc, therefore) by Hugh Collins Rice. The arrangement is entirely in keeping with the activities of the Second Viennese School, and specifically their series of concerts of the Society for Private Musical Performance.

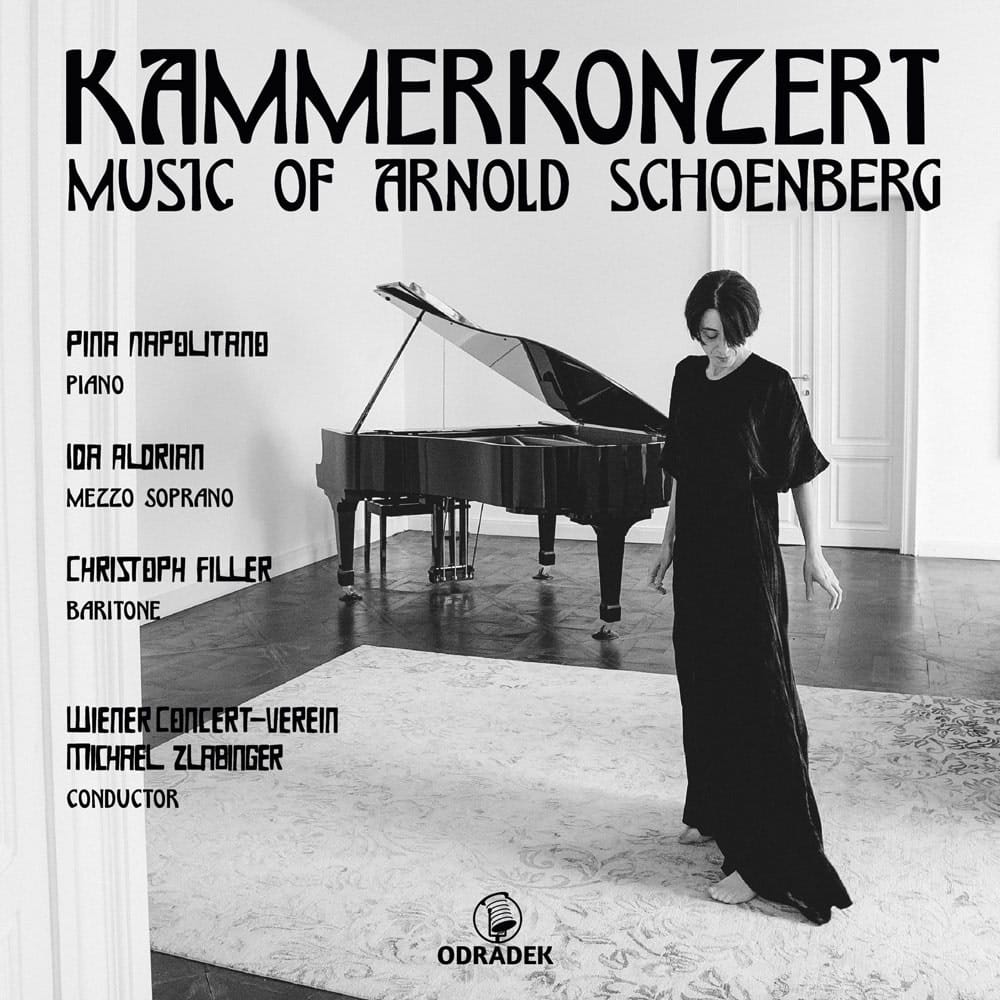

Schoenberg's Op. 15 Chamber Concerto (Kammerkonzert) was a turning point for the composer, and is scored for single strings and 10 winds (including three clarinets and two horns). Hearing the Piano Concerto arranged for a nearly identical line-up in an arrangement by Collins Rice (requested by the pianistic, Pina Napolitano) is revelatory: one hears every line.

Pina Napolitano is one of the finest living interpreters of the music of the Second Viennese School (Schoenberg, Berg and Webern, principally) and how her sensitivity shines in Schoenberg's Op. 42 Concerto.

Napolitano has a natural affinity for Schoenberg's way of phrasing, which leads to one some of the most musical Schoenberg playing available. There is an intimacy to this performance of the Piano Concerto that is most appealing; there is also something of the spirit of the dance here, too, in both first (Andante) and second (Molto Allegro) movements:

Schoenberg: PIano Concerto (i)

Schoenberg: PIano Concerto (ii)

Napolitano and Zlabinger find great power in the Adagio, wind contributions in particular expressive. The whole exudes cohesion, too, no easy feat in music as complex as this:

Schoenberg: Piano Concerto (iii)

The last movement is marked “Giocoso (Moderato),” and Napoletano and Zlabinger find the perfect balance. With Odradek's characteristically fine recording and the instrumental ensemble, the superb Wiener Concert-Verein, this is as immediately persuasive a performance of the Schoenberg Piano Concerto I know:

Schoenberg: Piano Concerto (iv)

There are several fine alternatives for the full orchestral version but the most useful is Maurizio Polini with the Berliner Philarmoniker under Claudio Abbado, in the first instance for the razor-sharp textures but also for the inclusion, on this video, of a score:

The Four Orchestral Songs, Op. 22 take us back to 1913-16 and are heard here in F. Griessele's arrangement for voice, flute, clarinet, violin, cello and piano. Christoph Filler, a name new to me, is a fine baritone. Although often overlooked, Op. 22 was Schoenberg's only completed work in the decade after Pierrot - the period wherein he took a deep look at his own musical language. The first song sets Edward Dowson (1867-1900) in a translation by Stefan George (1868-1933); the rest are by Rilke. All texts are of a somewhat visionary nature, and Schoenberg's response is more motivic than melodic: a kaleidoscope of fragments, if you like. The original is for large orchestra; again, the effect of this arrangement is to focus the mind on process while locating a new, delicate beauty. Here's the first and second:

Four Orchestral Songs, Op. 22: NO. 1, Seraphita

Four Orchestral Songs, Op. 22: No. 2, Alle, seiche dich suchen

I have to say I find the third particularly haunting, and Filler is particularly excellent here:

The arrangement is superb. Felix Greissle, Schoenberg’s pupil and son-in-law, was made in 1921 (the year Greissle married Gertrude Schoenberg) and so is very much of the piece's era. Given that, despite a large orchestra at his disposal, Schoenberg wrote in chamber music groupings, the work its superbly in small ensemble - a Pierrot ensemble, in fact. It is followed by an arrangement of an earlier piece, the “Song of the Wood Dove” from Gurrelieder arranged by the composer himself for a concert in Copenhagen in 1923, where it was, as here, coupled with the Op. 9 Chamber Symphony.

Ida Aldrian, a member of the Hamburg State Opera, is the rich-voiced mezzo in Odradek's superb recording. The arrangement includes a part for harmonium (a stalwart often Society's concerts); this performance is superb, Zlabinger using precise rhythm as a means of creating both depth and cohesion:

Finally, the Chamber Concerto (Kammerkonzert), Op. 9 is a glorious performance, often revelatory. Conductor Michael Zlabinger has clearly rethought the score from the bottom up; there are new textures here, and the performance exudes freshness, its many complex textures laid bare.

The final pages are incredibly exciting in this performance, and yet none of the detail is lost:

Another great exponent of this score was the much-missed Giuseppe Sinopoli. Unfortunately the DG performance with members of the Berliner Philharmoniker (originally coupled on LP with Manzoni’s Masse: Omaggio a Edgard Varèse with Pollini) is only available in segmented form on YouTube, so here's Sinopoli's Dresden recording (useful as it includes scrolling score):

A superb disc. Schoenberg's music requires concentration from the listener, but the rewards are massive. Performances are radiant; documentation detailed.

The disc is available for purchase at Amazon