18th Century Discoveries: John Abraham Fisher's Symphonies

Bright, shining, gallant music in sterling performances: a disc designed to bring joy

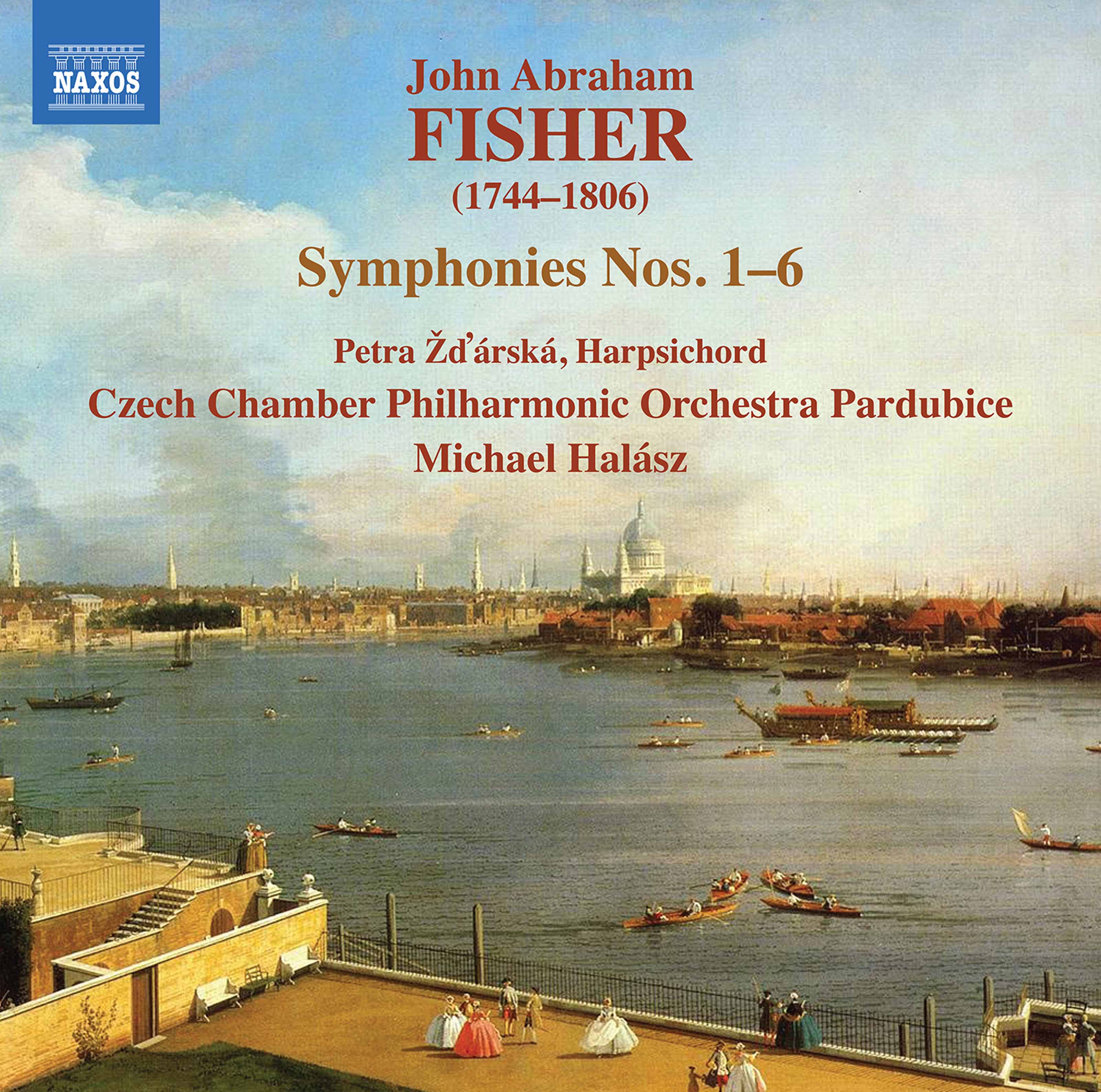

This is what exploration is all about: the discovery of bright, shining, gallant music in sterling performances. A disc designed to bring joy, what we have here is six symphonies by John Abraham Fisher (1744-1806).

Fisher was a virtuoso violinist who obtained a Doctorate in Music from Magdalen College, Oxford, in July 1777; he also wrote stage works for the Theatre Royal. Covent Garden. If you like music by J. C. Bach, William Boyce or Thomas Arne, you won't be disappointed.

The six symphonies here were published in London in July 1772 (there is a seventh, in manuscript and incomplete).

Here's the wonderful first movement of the Symphony No. 1 in E; it's a measure of the proportions of these works that it only lasts 2"22:

The finale of this First Symphony includes some delicious hunting horn-like passages: robust and fun:

Aficionados of the history of the symphony will know of the influence of the Mannheim School of the latter half of the 18th century on the form's development. Composers associated with Mannheim include Carl and Johann Stamitz and Christian Cannabich. The most famous trait was the 'Mannheim Rocket' because Mozart used it at the beginning of his Symphony No. 40 in G Minor; the style was characterised y dramatic crescendos and equally dramatic pauses. We hear some of these in Fisher's Third Symphony onwards, just as we hear an increasing freedom for the wind, especially in the Fourth, although the oboes and bassoons in the Andantino amoroso of the Third are a delight here:

What's nice is that in listening to this disc straight through, one receives an overview of Fisher's development as a symphonist: increasing length (from the five to six minute earlier symphonies, No. 4 is nearly a quarter of an hour) and increasing freedom of expression, heard in scoring and, indeed, in expressivity. And just listen to the sense of joy of the finale of Symphony No. 5, an Allegro di molto:

The performances here are by the Czech Chamber Philharmonic Orchestra, Pardubice, an orchestra that has recorded a number of volumes of Cimarosa Overtures for Naxos, as well as music by Michael Haydn and Leopold Koželuch. The harpsichord continuo is played by Petra Žd'árská. The orchestra under the expert direction of Michael Halász, plays with great suavité and is simply gorgeously recorded in Pardubice's Dokla House of Culture.