Dvořák: String Quartet No. 2 & Bagatelles

It is worth focusing on the String Quartet No. 2 here: Dvořák’s later quartets get all the glory, but the earlier ones - admittedly expansive - make for a great listen.

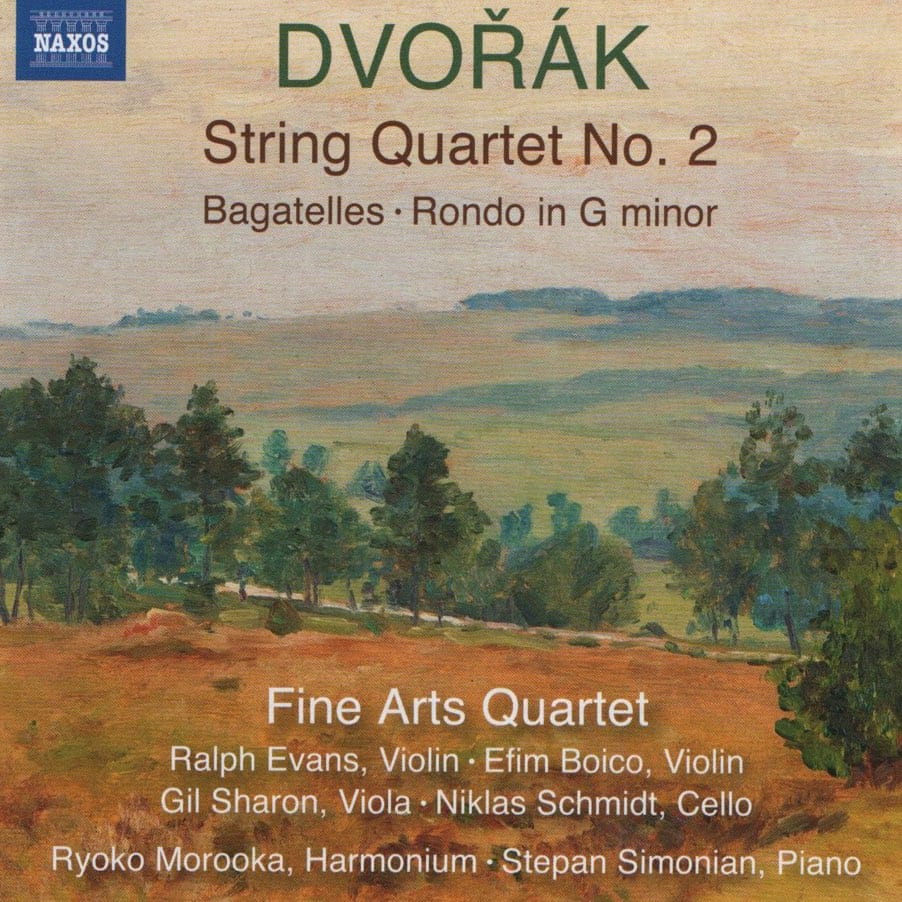

The quartet, in B flat major and with the catalogue number B. 17, was written in 1868-70. The three quartets, B 17-19, are heavily influenced by Wagner. The B flat, although following the four-movement form, is more stream of consciousness than sonata form in the first movement. The best listening strategy is to abandon oneself to the fertility of Dvořák’s invention. The Fine Arts Quartet is a fabulous ensemble (Ralph Evansm, Efim Boico, violins; Gil Sharon, viola; Niklas Schmidt, cello).

One can certainly hear that expansiveness in the first movement (13"12):

The Largo is magnificent, though. The Fine Arts Quartet have the full measure of the composers expressive way here, and as the music becomes more animated (six-seven minutes in), it is as if a ray of sunlight traverses the texture. All credit to Ralph Evans for traversing the high-lying passages so well around the ten-minute mark. At just under a quarter of an hour, this is another substantive movement, and some readers might find in the main theme an embryonic form of the slow movement of the composers Sixth Symphony, a full decade later:

Dvořák was always good at dances (think of all those Slavonic Dances - we found out they make great encores at our coverage of a Prom headed bytes great Iván Fischer, conducting his Budapest Festival Orchestra). They are nice and compact; this is less so, although it is by some measure the shortest movement of the quartet (at just under seven minutes):

The finale takes us back to the around quarter-hour movement format. The opening section, marked Andante, feels like a second slow movement, so intense is the Fine Arts' performance. Evans' violin sings eloquently, as does Niklas Schmidt's cello, while Gil Sharon makes a lovely, warm viola sound. All four parts intertwine perfectly. The shift to the Allegro giusto is exquisite, and exquisitely managed here. The texturesDvořák writes are often quite bare, and ut takes a fine quartet to honour them, to give them fragility rather than just have them sound skeletal. But the biggest take-away is Dvořák's unflagging invention. Untamed, yes, but glorious. Despite the quartets length, the music is so infectious one wishes it could go on longer:

The rondo in G-Minor (Op. 94/ B/ 171) was originally for cello and piano, and one can certainly hear that: it is like a filled-in version of a cello and piano duo. Niklas Schmidt is exceptional as a soloist here, his cello singing beautifully:

The disc begins with five Bagatelles, Op. 47 (B 79) of 1878 for two violins, cello and harmonium (this last played here by Ryoko Morooka, who enjoys a career as an organist).The publisher Simrock made an alternative for piano, but the harmonium's sustaining abilities make it really the only choice. Here's the lovely second Bagatelle, marked “Tempo di minuet: Grazioso”:

The fourth (“Canon: Andante con moto”)is for me the most satisfying, and the most beautiful:

A most satisfying disc full of loving performances.

This post effectively continues on from an early Classical Explorer post on Dvořák’s Piano Concerto (Exploring Dvořák). Naxos’ disc can be purchased from Amazon here; Spotify below.