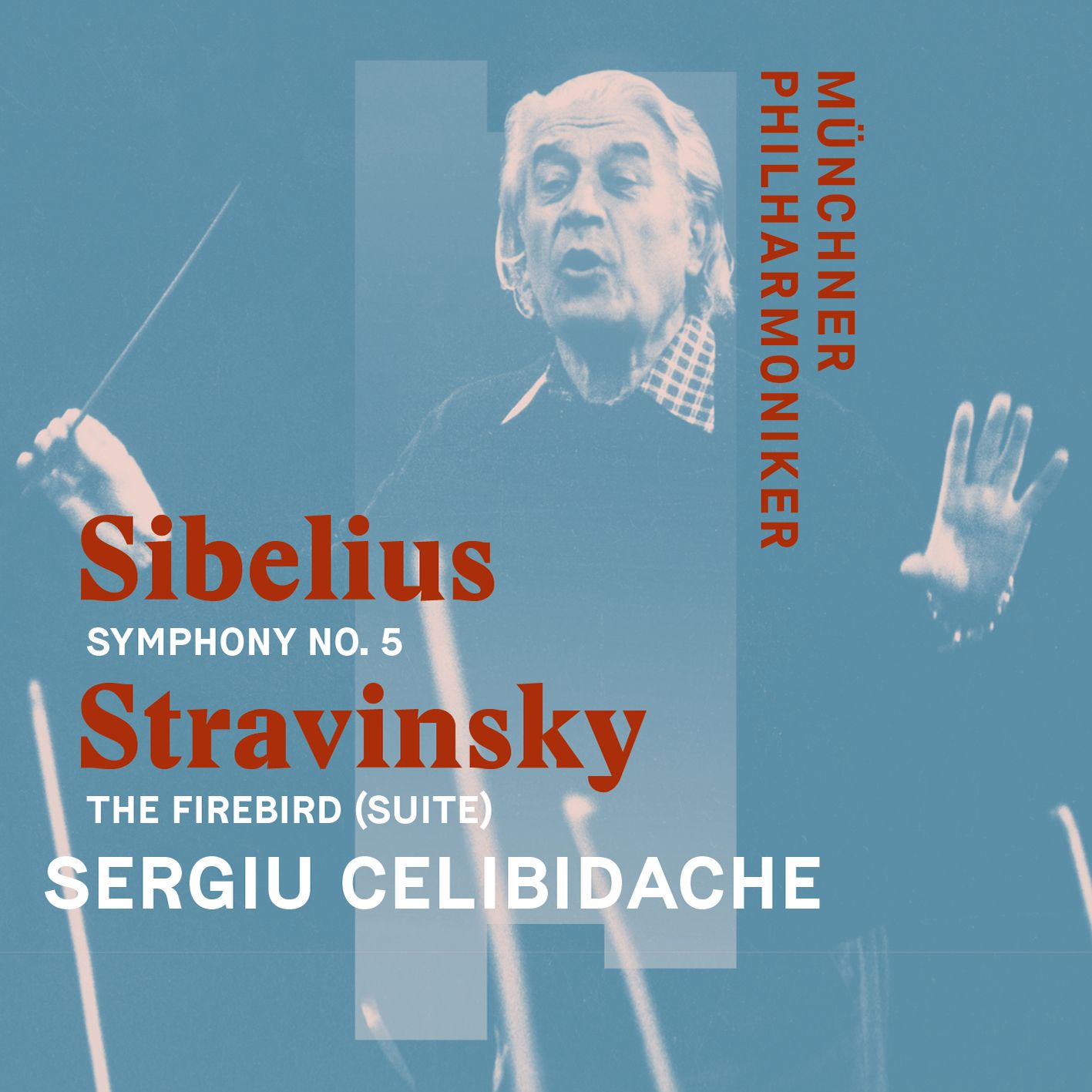

Celibidache in Sibelius and Stravinsky

Sergiou Celibidache (1912-96) is the greatest conductor you maybe haven’t heard of

Sergiu Celibidache (1912-96) is the greatest conductor you maybe haven’t heard of. He was very recording-shy (he famously said listening to a recording is like going to bed with a photo of Bridget Bardot: to paraphrase, all very well, but not the same thing, really). He did make some studio recordings - then stopped in 1950. From 1945 to 1952, he was Principal Conductor of the Berlin Phlarmonic Orchestra; but alter, he chose orchestras that would accommodate his rehearsal demands. From 1979 until his death in 1996, he led the Munich Philharmonic, the orchestra on this recording.

His theories of sound, his Zen Buddhism - this is a true musical maverick.

The Sibelius Fifth Symphony here is spacious, but concentraion never falters: imporotant in projecting the organic coherence of this work. The performance, given in Munich‘s Philharmonie im Gasteig on March 26, 1988, is rugged, and uncompromising. Here’s the first movement, which seems to inhale and exhale like a living organism. And as the music gets faster, how the woodwind dance. The increasing tempo over the course of the movement (tempo molto moderato - Largamente - Allegro moderato - Presto) is judged in masterly fashion, the final bars buzzing with energy and yet no sprint to the finish line (that was never Celi’s way). The slow movement isn’t quite that - the marking is Andante mosso, quasi allegretto. Celi’s moght not be the swiftest, but it moves (so, we do get the “mosso”), and once more that sense of organic expansion is everywhere. And the music’s opening out into those delicious woodwind staccatos is impeccable. Most remarkable is Celi’s way with the third movement is just as impressive: the horns, swinging Thor’s hammer metaphorically speaking (they continue so seamlessly and endlessly over their rising and falling octaves because they are split between two pairs of horns,like passing a ball between them) . The final chords (those huge orchestral chords that seemingly come at one randomly) are incredibly powerful (even if not every one is absolutely together.

Perviously, we have encountered Sibelius’ Fifth Symphony in complete sets by Klaus Mäkelä (Decca) and Osmo Vänska (BIS). Good to have a stand-alone Fifth more than worthy fo that company (although I will inevitably at some point include one that is persuasive at less controversial speeds).

The performance of Stravinsky’s The Firebird Suite (1919) comes from a love concert at Munich’s Herkulesaal on March 26, 1988.

What a magnificent sound Celi gets the cellos and basses to make at the opening of the Firebird’s. Introduction - double bass-heavy; and when they enter, ominous trombones (YouTube LINK to this and “L’oiseau de feu et sa danse”). Notice the painterly washes of sound in the Firebird’s dance, too.

The sheer beauty of the “Ronde des princesses” is a joy. Characteristically slow, it never drags; the “Danse Infernale du roi Kastchei” (simply known usually in English as the “Infernal Dance”) is a whilrlwind, orchestral tutti chords cutting like a knife, Stravinsky’s textures heard anew later in microdetail and yet with huge energy. And virtuoso contributions from the trumpet and xylophone.

The penultimate “Berceuse” is another miracle of sound. Like the introduction, it is slow but riveting: the bassoon sings its ever-so-Russian melody hauntingly; strings and harp move quietly in a loop. Out of this, it is the horn’s turn to sing, now the melody of the finale. Quiet, expectant - the beginning of a carefully-calibrated crescendo that takes us to the great, almost overwhelming statement on full orchestra that concludes the Suite.

This is a great performance of this work: the only one I can think of that come near it is one I heard live at the Henry Wood Proms many years ago now conducted by the equally great Günther Wand.

medici.tv is a great resource to learn more about Celibidache. There you will find performances of Brahms (with Barenboim), a Bruckner Seventh Symphony and Mass in F-Minor, Tchaikovsky, Schumann, and two films: Wolfgang Becker’s Sergiu Celibidache: The Triumphant Return and Jan Schmidt-Garre’s You don’t do anything, you let it evolve (this last by the same director as Fuoco Sacro, a film about Ermonela Jaho, Barbara Hannigan and Asmik Grigorian, covered in this recent post).

If this is your “in” to Celibidache, a whole brave new world awaits!