Beethoven's “Fidelio” at the Barbican

Laurence Equilbey left us in no doubt as to the power of this piece

Beethoven Fidelio (concert staging). Cast; accentus; Insula Orchestra / Laurence Equilbey. Barbican Hall, London, 11.05.2022

Production:

Director – David Bobée

Assistant Director – Nicolas Girard-Michelotti

Costume designer – Sabine Siegwalt

Libretto revisions – Beate Haeckl

Cast:

Florestan – Stanislas de Barbeyrac

Leonore - Sinéad Campbell-Wallace

Don Pizarro – Sabastian Holecek

Rocco – Christian Immler

Marcelline - Hélène Carpentier

Don Fernando - Anas Séguin

Jacquino – Patrick Grahl

Prisoner I (tenor) - Lancelot Lamotte

Prisoner II (bass) - Matthieu Heim

Fidelio is a notoriously difficult opera from a number of angles: the demands made on soloists (particularly the two principals), the number of versions (Leonores) that led up to the final Fidelio and their impact on the final outcome; and the successful structural move from the opera buffa of the opening to the grand opera of the finale. Hearing the opera without interval, as was the case here, made that two hour-plus arc all the more memorable.

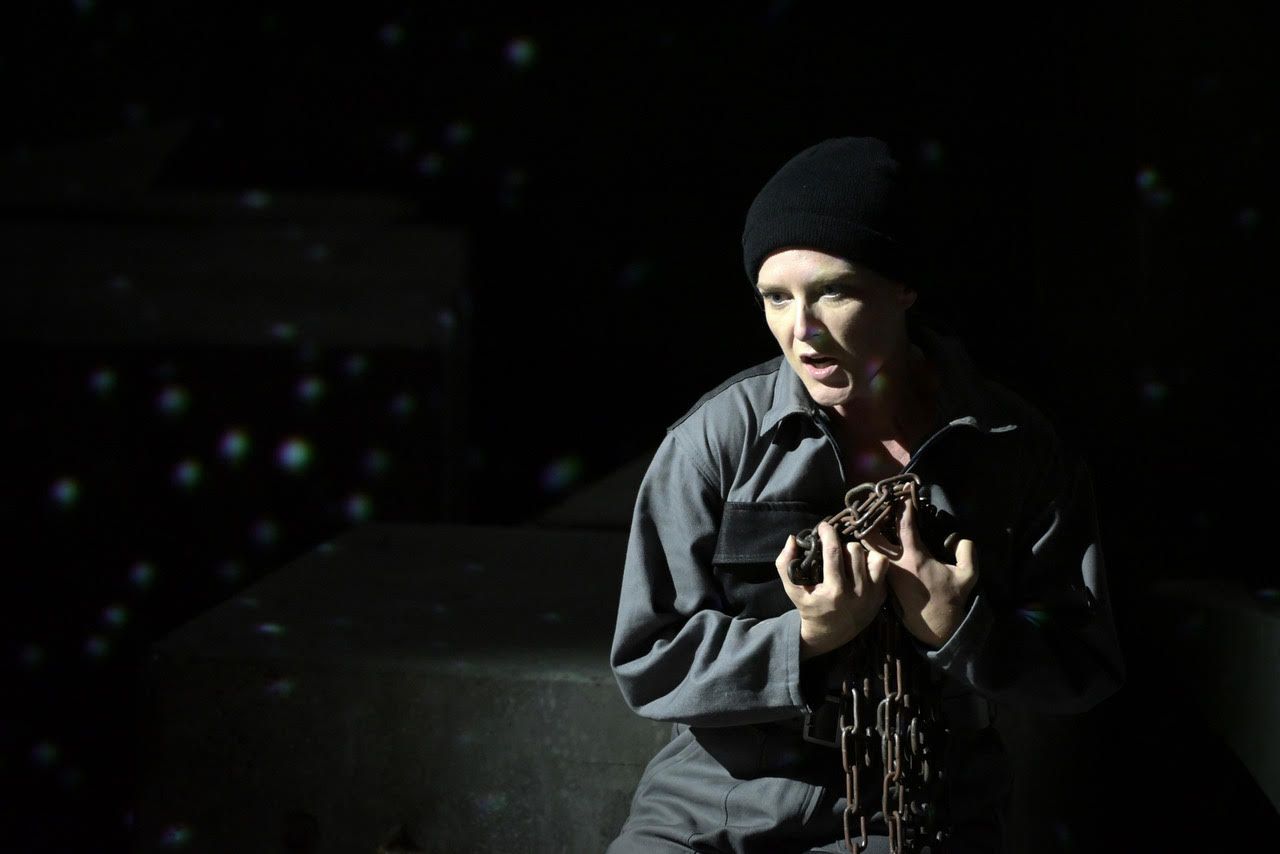

The wording in the description of what this performance ‘was’ is significant: ‘concert staging’ as opposed to ‘semi-staged’. So there was little to no staging or props (the odd cup, a gun, some chains and so on), but characters were in full costume (or, in Florestan’s case, a seemingly actively disintegrating costume). Laurence Equilbey and David Bobée have collaborated successfully before (on La Nonne songlante) and in the fuller staging to be heard in various venues in Europe, concrete blocks and rusted metal will conjure a collapsed world Bobée has suggested that light and truth are locked underground with Florestan, with the characters above ground trying to navigate a world without the benefit of a compass. This might all sound familiar today, and Bobée, here more via costumes and character placement around the performance space, indeed suggests that a grayness hangs over the vast majority of the opera. Lighting was used effectively, from the darkness of the Prisoners’ Chorus to the hope of the finale. As Equilbey put it to me in an article printed in Opera Now, ‘In the end, it must be understood that only the alliance of citizens and politics can provide a solution to conflicts and injustices’.

Dialogues have been tightened for dramatic effect; and indeed, the whole worked perfectly as a dramatic entity, underpinned by Equilbey’s deep understanding of Beethoven’s processes. Using original instruments gives a certain transparency to textures, plus myriad extra colours (most noticeably, perhaps, in the horn quartet’s contribution to Leonore’s famous aria ‘Abscheulicher!,’ where hand-stopping makes such a vital difference; a colour as opposed to a black-and-white image, really). Another example: the sheer darkness of timbre created at the opening of the second act through the low wind timbres. Not to mention the dark buzzing of a contrabassson; or the oboe’s tart shaft of sonic light in Florestan’s great aria.

After numerous successes in the opera house – including a remarkable Weber Freischütz - Laurence Equilbey turns her attention to Beethoven’s magnificent creation. Equilbey realises that to succeed this is far more than a two-singer show: there is not a single weak link here. The opening scene between Jacquino and Marcelline shone, Patrick Grahl’s ardent (and sometimes comedic) enthusiasm the perfect foil for the more layered character of Marcelline. And it is at this very role we find a singer of huge talent: soprano Hélène Carpentier, a voice of both purity and strength with acting abilities to act. It is rare to hear a Marzelline that can hold her own against the ‘other’ soprano – Leonore/Fidelio her/himself. Yet here, time and again we felt the importance of Marzelline’s contribution to the ongoing drama – which meant her contribution to the radiant closing scene enabled us to resonate with her disappointment while equalling Campbell-Wallace's cries of ‘Nie’ (Never!) in Beethoven’s concluding hymn to liberty. Worth noting that the two solo prisoner roles (Lancelot Lamotte and Matthieu Heim) were executed to the same level of excellence (perhaps not too surprising considering the choir is accentus; the choral contributions were consistently impressive).

Making his role debut as Florestan, Stanislas de Beyerac was almost impossibly touching. Clad in rags, a shadow of his former self, his realisation that there is hope through the revelation of his wife’s identity and his subsequent release offers, indeed, hope for us all. His negotiation of the great opening aria of the second act (‘Gott! Welch Dunkel hier!’ began quietly; we see him discombobulated, potentially hallucinating. Equilbey’s conjuring of the most magical pianissimi was, for sure, a major constituent in this passage’s success, but de Barbeyrac’s living of the part was remarkable. Although not a role debut (she previously sang Leonore with Irish National Opera), Campbell-Wallace's interpretation of Fidelio/Leonore had real freshness about it. She is a strong soprano, yet her lower register is so strong (Beethoven does make considerable demands down there, too). Her voice itself is remarkably free, and absolutely equal to Beethoven’s sometimes cruel demands (that final scene!), her stamina remarkable, the final reveal (‘Töt’ erst sein Weib’) stunning in its vocal heft. The Florestan/Leonore duet, ‘O namenlose Freude,’ found both of them at their very best.

One character that commands the stage in no uncertain terms is Don Pizarro, the opera’s personification of evil, nowhere more so than in his two great moments (one per act): ‘Ha! Welch ein Augenblick’ and ‘Er sterbe!’. Austrian bass-baritone Sebastian Holecek has a voice to match his stature (which bodes well for his Klingsor, due in Dornach, Switzerland next year). The Rocco, Christain Immler, has previously impressed as the Hermit and Voice of Samiel in Freischütz with Insula; if anything this was even finer offering a very human Rocco torn between materialism (his ‘Geld’ - money – aria) and a deeper humanism. This Rocco was a rich and complex character. Finally, Anas Séguin, a brilliantly just and firm Don Fernando – the hug between Fernando and Florestan actually felt heart-felt.

It will be interesting to see a fuller staging of this in Paris next week; but there is no denying the emotional impact of Equilbey’s reading. Beethoven’s opera triumphed. The Royal Opera Fidelio of 2020 is still surely in many Londoners’ consciousness; and of course many Fidelios (if such is indeed the plural) did not make the light of day due to the pandemic. This was, though, a reminder of Beethoven’s genius: and Equilbey left us in no doubt as to the power of this piece, Time and time again, be it in Beethoven, Weber, or Schumann, or others, she proves that in rethinking the familiar and meeting it anew, the revelations necessarily follow.